You Might Be Missing These Hidden Signs of Iron Deficiency

Emma Brooks September 2, 2025

Iron deficiency often hidden signs iron deficiency, affecting energy, mood, and daily life without clear warning. Explore the subtle symptoms, discover who’s at risk, and learn practical dietary and clinical insights to protect your wellbeing in this in-depth guide to iron health.

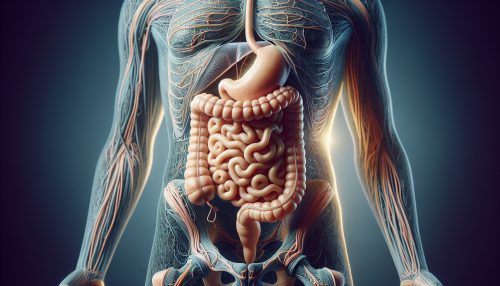

Understanding Iron’s Essential Role in the Body

Many overlook just how critical iron is for the body. This mineral supports the creation of hemoglobin in red blood cells, which carry oxygen throughout the body. When iron levels drop, the body cannot deliver adequate oxygen to cells, causing fatigue and reduced concentration. Even mild iron deficiency can lower productivity, making daily tasks feel unexpectedly harder. Iron is also involved in immune function, enzymatic processes, and supports healthy cognitive development, showing its importance extends far beyond preventing anemia.

Low iron is a common global issue, especially among women, children, and those with certain health conditions. There are two primary types of dietary iron—heme and non-heme. Heme iron, found mainly in animal products, is easier for the body to absorb. Non-heme iron, found in plant-based foods like spinach and lentils, requires more effort from the digestive system. Nutritional guidelines often recommend diverse sources to maintain optimal levels, which can be a challenge for vegetarians or those with certain dietary restrictions.

People may not realize that hidden signs iron deficiency requirements change with life stages. Children need it for growth, teens during rapid development, and adults for ongoing repair and energy. Pregnant individuals require even more to support fetal development. Iron’s impact on mental and physical health is profound, making awareness of its role a fundamental part of self-care. Guidance from nutrition experts and health organizations highlights the need to understand intake sources and absorption factors for optimal health.

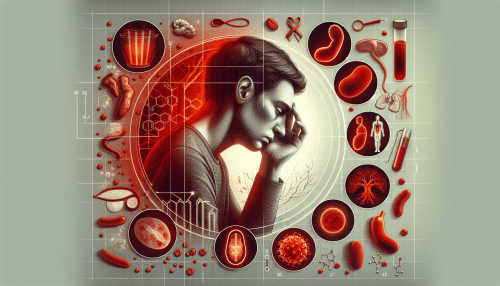

Subtle Signs You Might Not Recognize

Iron deficiency doesn’t always announce itself loudly. Many symptoms appear subtle at first—like unexplained tiredness, pale skin, or shortness of breath during regular activities. Some may experience dizziness or headaches, which are easily attributed to busy lifestyles or minor illnesses. These early warning signs often go unnoticed until the problem escalates. Catching these clues early can help prevent development of full-blown anemia or complications that impact long-term health.

Another often-missed symptom is unusual cravings, such as the urge to chew ice (a sign known as pica). Brittle nails, dry or thinning hair, and cracked corners of the mouth also occur more commonly than realized when iron is low. Restless leg syndrome, characterized by the urge to move your legs at night, has also been linked to hidden signs iron deficiency deficiency in several studies. Monitoring these signs and discussing them with a provider may lead to earlier intervention.

Cognitive changes can be particularly elusive. Difficulty concentrating, memory lapses, or feeling mentally sluggish could be the result of declining iron stores. In children and adolescents, this may manifest as trouble with schoolwork or developmental delays. Recognizing these patterns, especially when combined with other mild symptoms, empowers individuals to seek evaluation and address root causes before more serious problems develop.

Who Faces Increased Risk for Iron Deficiency?

Certain groups face a higher chance of developing iron deficiency, and knowing these risk factors can guide preventative steps. Women of reproductive age, due to menstruation, frequently encounter chronic low iron. Pregnancy increases demand significantly, requiring dietary assessment and sometimes supplementation with expert oversight. Young children, particularly during growth spurts, and teenagers also experience elevated need for dietary iron to support development.

Vegetarians and vegans are more likely to experience low iron status due to reliance on non-heme iron, which is harder to absorb. People with digestive conditions such as celiac disease, Crohn’s, or ulcerative colitis may suffer poor absorption, even with adequate dietary intake. Blood donors and those with a history of heavy periods may face recurrent deficiencies if extra intake is not prioritized. Screening for these groups is often recommended by global health authorities.

Certain medications, including proton pump inhibitors and antacids, can impact iron absorption when used regularly. Those recovering from surgery, injury, or those with chronic kidney disease may also need closer attention to iron levels. Understanding personal risk factors supports collaboration with healthcare teams to develop individualized nutrition or supplementation plans, ensuring health is maintained while minimizing complications.

How Diet Influences Iron Absorption

Diet is the first line of defense against iron deficiency. Animal-based foods like lean meats, poultry, and seafood offer highly absorbable heme iron. For those following plant-based diets, lentils, beans, tofu, fortified cereals, and leafy greens can help increase non-heme iron intake. However, it’s not just about eating iron-rich foods; combining these with vitamin C sources—like citrus fruits or bell peppers—can enhance absorption. Some staple meal combinations, such as spinach salad with orange slices, are popular for this reason.

Certain substances inhibit iron absorption. High amounts of calcium, polyphenols in tea and coffee, and some whole grains containing phytates can all reduce dietary iron uptake when consumed at the same meal. Spacing out iron-rich meals from dairy or sipping tea and coffee an hour before or after eating are simple adjustments that may boost overall iron status. Nutrition counseling and meal planning can help clarify these relationships and personalize approaches to maximized absorption.

Some individuals benefit from fortified foods or supplements under medical advice. Over-supplementation is not without risk, as excess hidden signs iron deficiency can be harmful, particularly for those with genetic predispositions to iron overload. The majority benefit most from dietary adjustments, careful food pairing, and, when necessary, targeted short-term supplementation monitored by healthcare providers. Ongoing research continues to refine recommendations for different populations and lifestyles.

Testing and Diagnosing Iron Deficiency

Testing for iron status goes beyond a basic blood count. A healthcare provider will often recommend measuring serum ferritin, transferrin saturation, and total iron binding capacity to get a full picture. Ferritin best reflects stored iron while hemoglobin reveals the impact on red blood cells. Interpreting these values together provides a more accurate assessment of iron reserves and active deficiency or anemia. The combination of lab results and physical symptoms guides next steps in management.

Individuals experiencing persistent symptoms, who belong in high-risk groups or have dietary limitations, may be advised to undergo regular screening. Testing is especially important for pregnant individuals and growing children, as untreated deficiency in these groups can have long-term consequences for growth, cognitive development, or pregnancy outcomes. After diagnosis, healthcare professionals tailor restorative plans that might include dietary changes, supplements, or addressing potential causes of blood loss or malabsorption.

Public health guidelines highlight that self-diagnosing or supplementing without testing can lead to more harm than good, especially since iron overload is possible in certain genetic conditions. A professional evaluation ensures the right diagnosis and the most effective, safe approach for restoring balance. The goal is identifying deficiency early so that intervention is effective and health is maintained over the long-term.

Maintaining Healthy Iron Levels for the Long Run

Maintaining optimal iron levels is a lifelong process, not a one-time fix. A diet that always incorporates diverse iron-rich foods, paired with vitamin C, can help support daily needs. For those with increased or ongoing risk, working with a dietitian or healthcare provider to develop individual meal plans and monitoring routines is often beneficial. Lifestyle awareness, such as meal timing and careful management of inhibitors, adds a practical dimension to maintaining balance.

Some choose to track their energy, focus, and overall wellbeing as indirect markers for iron health. Slight changes in sleep quality, stamina, or cognitive sharpness may reflect shifting iron status. Engaging in regular screenings, especially for those at higher risk, is an important preventive step. Personal experiences often guide subtle tweaks such as rotating new protein or plant-based foods into weekly meals.

Education remains central. Schools, public health campaigns, and community programs regularly promote iron enrichment and awareness initiatives. Continuing to learn and adapt dietary habits throughout different life stages, staying aware of symptoms, and acting early make a significant difference in preventing silent but impactful deficiencies. Ultimately, informed choices support both short-term vitality and long-term health and well-being.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Iron Deficiency. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/infantandtoddlernutrition/micronutrients/iron.html

2. National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. (n.d.). Iron: Fact Sheet for Consumers. Retrieved from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iron-Consumer/

3. World Health Organization. (n.d.). Anaemia. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/anaemia

4. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. (n.d.). Iron Deficiency: Symptoms and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.eatright.org/health/wellness/preventing-illness/iron-deficiency

5. American Society of Hematology. (n.d.). Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Guide to Diagnosis and Management. Retrieved from https://www.hematology.org/education/patients/anemia/iron-deficiency

6. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (n.d.). The Nutrition Source – Iron. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/iron/